The teaching of phonics has changed in recent years with the introduction of explicit, systematic synthetic phonics and the phonics of yester-year is no longer enough for an emergent reader and speller.

When I think of my current understanding of phonics – that it needs to be taught explicitly and systematically – I reminisce about my early teaching career when I was blessed with my very own class of 4.5-year-olds. They were students who had English as a second language and I knew that phonics was a necessity. However, the phonics I taught then was not the same phonics I now know and teach.

At the time, the teaching of phonics was simply known as the alphabet with each letter introduced at a very slow pace. A letter sound per week was the norm. There was no evidence of blending and segmenting; in fact, my phonics program consisted of letter names, handwriting, initial sounds and lots of craft activities. I thought I was teaching phonics. And I wasn’t wrong; it was just not enough.

Understanding the purpose of the teaching of phonics can provide clarity when programming a phonics lesson for the purpose of reading and spelling. So, what do I know now, that I wish I knew when I first started teaching phonics to my 4.5-year-olds?

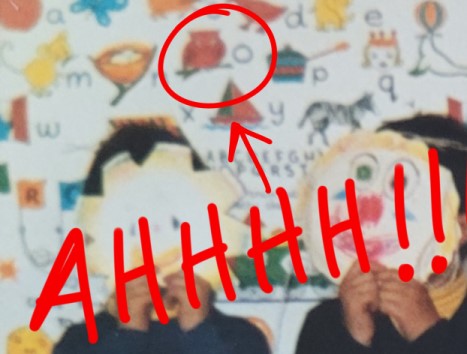

Caught red-handed! That ow l definitely isn’t

Caught red-handed! That ow l definitely isn’tI now understand that teaching phonics is more than just teaching the 26 letters of the alphabet. It is ensuring that the alphabetic code is introduced to children as quickly as possible to give them the opportunity to successfully decode unfamiliar words. This alphabetic code is mapped to the 44 English phonemes and while the code is complex, it is crucial knowledge for reading and spelling. The complexity is highlighted through the 150+ spelling choices to represent the 44 phonemes using our 26 alphabet graphemes.

As teachers and parents, it is important to empower ourselves with this knowledge so that our students can be given the best start on their reading and spelling journey. This best start also equates to pace; this was my biggest change in the programming of phonics for my students. The more letter sounds taught, the quicker we can move to the skills of blending and segmenting.

Are you still introducing letter sounds at the pace of 1-2 per week? If so, let me set you a challenge to increase the pace to 3-4 letter sounds each week. I wish someone had nudged me earlier to put an end to the drawn-out sound of the week that had plagued my phonics instruction for so long!

It’s ok to be flexible with the sequence of the letter sounds. Make it work for you and your students. You may occasionally need to introduce specific letter sounds earlier because they are required for reading in a decodable book. Don’t be afraid to introduce alternative spellings to the digraphs that are not part of your sequence. Look at your students’ names and introduce alternative spellings to phonemes that are found in their names. For example, Cindy, Joseph, Charlotte, Christopher.

You’ll find more tips on teaching alternative spellings in Shirley Houston’s blog How to Teach Alternative Spellings.

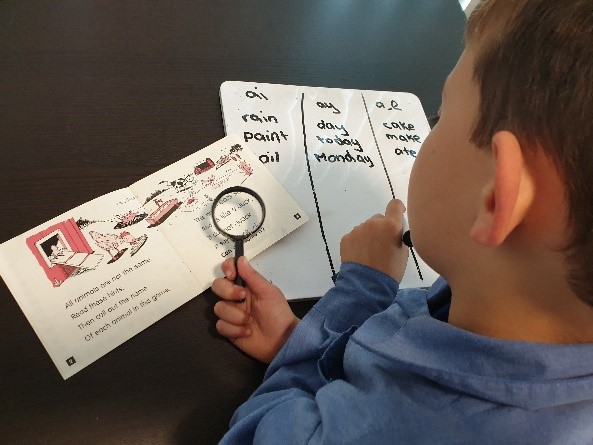

Short Sharp Practice is a 10-minute daily routine to practise the synthetic phonics skills you have taught so far – letter sound recall, blending, segmenting and tricky words. Each day can focus on just one of these skills for the daily routine. The aim is to consolidate the learning and build automaticity.

My daily practice can be as simple as this:

The Phonics Lessons from Phonics Hero will support you in every step of the Short Sharp Practice daily routine.

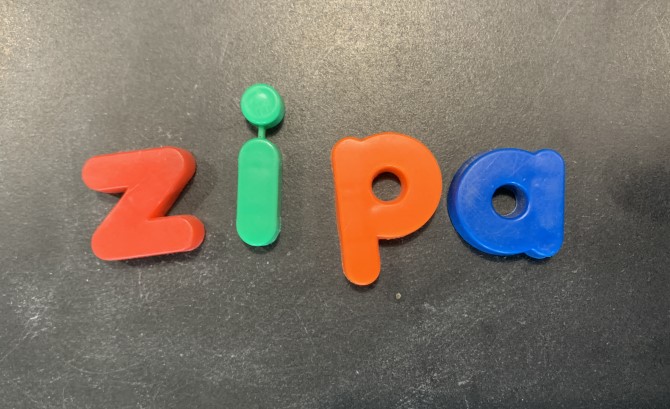

Pronunciation of letter sounds has become my mission as I both teach students to read and spell and mentor other teachers in synthetic phonics. Some children tend to add a schwa (/uh/) to the end of a speech sound, which can impact our children’s ability to blend and segment words correctly. For example, the unvoiced grapheme ‘p’ is often pronounced with the schwa /p/uh/. If not demonstrated correctly, students may say the phonemes for a word such as ‘zip’ a /z/uh/ – /i/ – /p/uh and blend them to say the word ‘zipper’. The blending has produced an incorrect word.

Incorrect pronunciation also impacts segmenting. Some students would write additional graphemes when spelling a word even though their segmenting of the spoken word was correct. The additional graphemes represented the schwa that was inserted at the end of the phoneme.

The extra schwa can play havoc with spelling!

The extra schwa can play havoc with spelling!Phonemic awareness is the ability to listen to the individual phonemes in words as well as manipulate phonemes to create new words. The research is clear that phonemic awareness is crucial for reading and spelling success and should be an integral part of any synthetic phonics program.

Focus on phonemes anywhere in a word, not just the initial phoneme to a word. Phoneme fingers are useful as students can visualise the position of a specific phoneme.

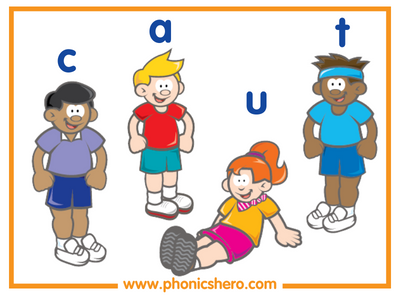

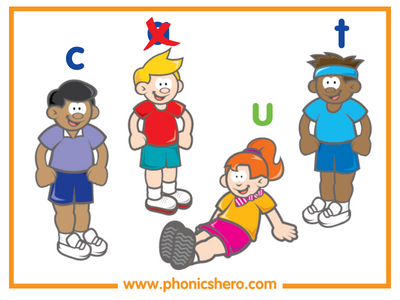

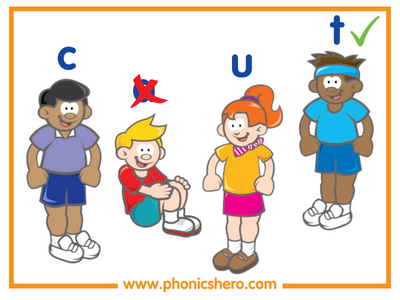

The image below illustrates how a student isolates the individual phonemes in /cat/ as well as highlights the initial, medial and final phonemes. Look how simple it is when students are asked “Where can you hear the /a/ phoneme?”

We continue in this manner manipulating phonemes to create new words cat-cut-but-bug-bag-bat-fat.

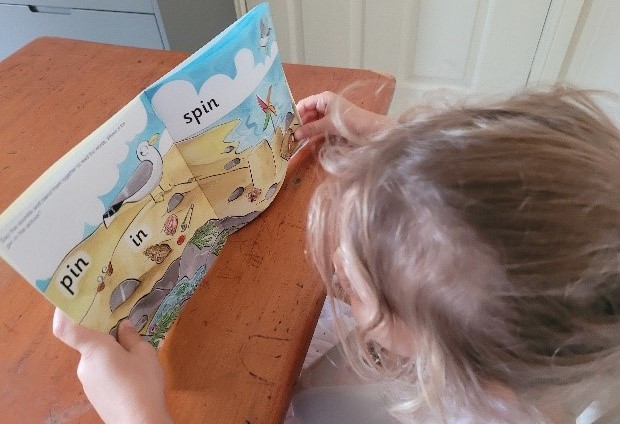

You know your sounds. Now let’s read these words.” Tina DiMauro, 1988

This direction to my students in my early teaching career still haunts me. Here’s what I’ve learnt since:

The team at Phonics Hero have lots of tips and activities on blending and segmenting.

There has been a change of the guard in reading to an acceptance of synthetic phonics as a key component. Change brings knowledge. Let’s empower ourselves and each other with the knowledge of synthetic phonics so that soon we need not say “I wish I knew this before I started teaching phonics.”