I’ve been asked if you should teach upper or lower letters first, a few times recently, so in this month’s blog post I’ll address the debate and the impact of your choice on reading and spelling. I’ll also make recommendations for best teaching practice.

The Argument for Teaching Upper Case First

The Argument for Teaching Upper Case FirstThe ‘upper case first’ camp believe that ‘capitals’ are easier to identify, differentiate, and draw. They have a simpler visual structure than lower case letters. The only letters that are likely to cause orientation-based confusion are ‘M’ and ‘W’. The ‘capitals’ are predominantly formed with straight strokes (which are developmentally easier to draw than curves) and are all written on the lines on lined paper. Upper case letters are relatively common in environmental print e.g. street signs.

Certainly, research (Worder & Boetcher, 1990) suggests that young children usually recognise more upper case letters than lower case, have a preference for upper case writing and write upper case letters better than lower case between the ages of 4 and 6. But is that because so many carers teach children to recognise and use upper case letters before they even start formal schooling?

The Argument for Teaching Lower Case First

The Argument for Teaching Lower Case FirstI would argue that the practice of teaching upper case letters first, because they are considered ‘easier’, is more of a ‘societal tradition’ than sound educational practice. Upper case letters have minimal connection to early literacy skills; 95% of written text is in lower case letters. When children’s parents read books to them or when they attempt to read for themselves, children will not typically see text written in upper case. Visual recognition of lower case letters will be more helpful than that of upper case. This is why Phonics Hero teaches lower case letters in isolation and in isolated words (get access to free resources when you sign up for a Teacher Account).

The upper case letters have a special, important job and should be taught in context. They show the start of a sentence or a name. ‘Capitals’ are best taught initially as the first letter in a child’s name. They are often the first and only capital letter in product names and shop signs so attention can also be drawn to them here. A name is usually only written completely in upper case when it has to be seen from a significant distance. Once the child is able to read or write a sentence, attention should be drawn to the need for an upper case letter at the beginning.

If we initially teach a child to write words all in upper case, we have to later teach him that it was actually totally incorrect practice and try to get him to ‘unlearn’ it. Learning is much easier than ‘unlearning’. This is why many students continue to use capitals incorrectly in words. Many programs, including Phonics Hero, use lower case letters to teach letter-sound correspondences and upper case letters to teach alphabet letter names.

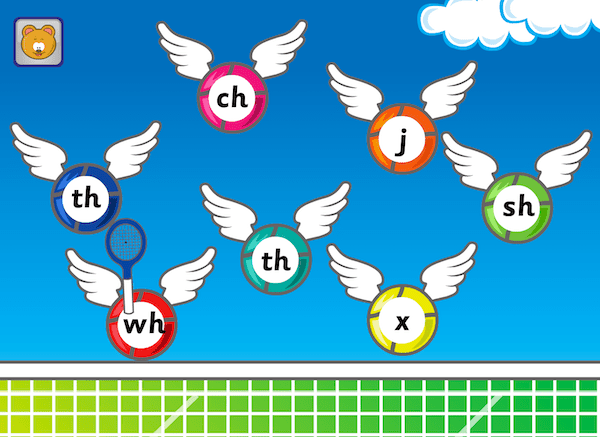

A lowercase letters game from Phonics Hero.

A lowercase letters game from Phonics Hero.This is because knowledge of the alphabet names does not help the child to ‘sound out’ words but will become useful when describing a spelling such as the ‘c’, ‘k’ or ‘ck’ spelling of the sound /k/.

One argument people make for teaching upper case letters first is that they’re easier to form, but, actually, all of the types of hand movements are required by both upper and lower case. Upper case letters have more starting points and require more strokes/pencil pick ups, so are actually harder than lower case to draw. There are more diagonals in upper case letters, which is developmentally challenging. Consequently, it makes perfect sense to start writing with lower case letters. If cursive writing is being taught from the outset, it makes even more sense.

Logic suggests that we should build the essential foundations of sound and shape first, then add the ancillary concepts, such as capital letters and letter names. When you need to teach upper case letters for writing, explicitly teach them as ‘partners’, side by side. Provide a wall display and desk mat with both upper and lower case letters shown next to a relevant picture the child will recognise, like below. Many alphabet books, such as Dr Seuss’ ABC do this.