It’s common knowledge that the explicit teaching of systematic, synthetic phonics is critical for children to become strong readers and spellers. But what about those children whose first language isn’t English? How do you accommodate for those students of English as a Second Language (ESL) who don’t have the same breadth of vocabulary and ‘ear’ for another language’s sounds?

As a teacher in Hong Kong, whose classes include both native English speakers and second language learners, I regularly find myself counselling parents through my, their and our concerns and fears about their children’s reading development.

Counselling is a deliberately chosen word here. And so is fear. Reading development can be a cause of great concern for both parents and teachers, and reassurance and guidance is often needed.

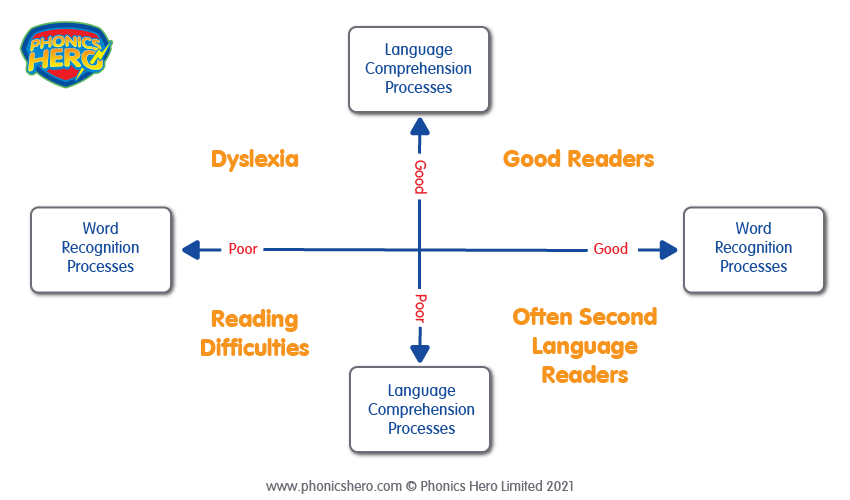

The Simple View of Reading is a very useful model for teachers as it explains why children need both word recognition processes (phonics) and oral comprehension skills to become a skilled reader, and what happens if one or both of those skills is weak.

On a practical level, I’d say that progress in literacy is also a result of motivation. At the lower primary level, the drive to improve reading comes from both parents and students – but mostly parents. However, within my mixed classrooms, that parental motivation is not universal.

The most frequent question from L2 (those learning English as a second language or ESL) parents is “How can I get my child to read more?” Conversely, the most common statement from L1 (native learners) parents is “We don’t really worry about it, we concentrate on (here, you can insert any other subject but English).”

Parents of L1 students frequently assume that their children will have natural advantages over L2 learners. And, of course, there are areas where this is true.

For example, as shown in the Simple View of Reading, it is very common for L1 students to have a better understanding of the overall meaning of a text – wider and deeper exposure to vocabulary gives them an advantage.

When it comes to pronunciation, L1 learners may have a more nuanced appreciation of sounds, and a greater tolerance to variation of accent.

Overall, though, the difference in parental priorities means that, perhaps ironically, at lower primary levels, it is common for many of the L2 learners to be stronger readers than the L1 learners. And why is that? Practice means progress!

Of course, I’m speaking in generalities here, but in my experience, it is common enough to have practical implications for teaching phonics to mixed L1/L2 classes.

For any given word, acceptable pronunciation is more likely to be a problem for L2 learners. However, this does not necessarily hamper reading comprehension – only reading aloud.

The massive variation in pronunciation both within and between native English-speaking countries, and English in its many forms as a second language, shows that pronunciation does not have to be uniform for phonics to be effective.

In a recent class, the word ‘crisps’ was being taught. This is very difficult for the non-native English speakers of my class to pronounce. Yet, by the end of the lesson, they were as successful in identifying the word in a text and understanding its meaning as the native speakers.

More importantly, for phonics, the ability to discriminate between sounds and internally apply acceptable pronunciation, is actually the key to decoding.

We should see pronunciation (often constrained by unfamiliar tongue or lip movements and positions), as only the physical output, and last in line, of an internal decoding and comprehension process.

For teachers, this means that modelling the language consistently and within acceptable range (i.e the input for the students is strong, so they can internalise accurately), is time better spent than over-correction of student pronunciation.

Phonics Hero’s no-prep Phonics Lessons are a great resource for teachers, as they offer video and audio support for pronunciation of all phonemes.

However successful decoding is, it can literally be meaningless.

It is common to see an L2 reader decode a text in full, but have little understanding of individual words and overall meaning. They appear to be reading fluently, but in fact have little comprehension.

It is also common to see an L1 reader struggle with decoding, but gain a good understanding of the text if the teacher prompts them through the decoding process.

In the mixed classroom, we as teachers can use this to our advantage: this situation gifts us the opportunity for peer learning. Strong decoders can be asked to model the synthesizing of the individual sounds, and those with stronger vocabularies offer definitions, uses and meaning in context. A win-win situation!

Of course, the search for meaning stops when we get to nonsense words.

Ask a new learner of English which word is real “cog” or “cag”, and many will just have to guess!

Ask a new learner of English which word is real “cog” or “cag”, and many will just have to guess!The use of nonsense words in phonics has its advocates and detractors. Primarily, it is claimed that nonsense words are the best way to check that decoding skills are being learned, as to achieve correct pronunciation, students must use phonics skills and not memory or context. There are arguments to be made on both sides.

Personally, I try to avoid nonsense words for lower primary classes. I think both L1 and L2 learners are better served, and less confused, by learning phonics with words that they can actually use later.

The talented, but vocabulary poor, decoders (typically a second language learner), have no use for the nonsense words: their decoding doesn’t need practice and if vocabulary is limited, almost every word may as well be a nonsense word!

And if decoding is poor, why waste precious time trying to decode nonsense words, when decoding real words will open up real meaning to the student?

I see little to be gained with nonsense words for younger students.

Here’s where Phonics Hero comes in. We spread the material from Phonics Hero over three years, using both the online games and printed material as the core to our programs. We find that, on average, progress is similar across L1 and L2 learners.

And so to return to where we started: parental concerns and fears. Reading progress doesn’t develop as naturally for native English speakers as L1 parents may hope, and being a second language learner may not be the impediment some parents fear.

What is most apparent from my classes is that with phonics and literacy – as with most things – it is practice and application that makes progress.

Overall, within my mixed classrooms, we are able to have very balanced phonics instruction for our L1 and L2 students. By taking into account the impact of differences in parental priorities and implementing a sound phonics program and resources, good teacher modelling and peer learning, we can mitigate what may have first appeared to be natural advantages and disadvantages of L1 and L2 students.

For those of you interested in learning more about the role of explicit phonics instruction in bilingual education and the science behind biliteracy, check out The Science of Reading in Dual Language.