Using letter-sound correspondences is the most reliable strategy for spelling and reading words, however, there are times when a student will come upon ‘tricky words’ and cannot rely on this strategy. These words are tricky because they cannot be spelled or read phonetically using the letter-sound correspondences known by the student. Often, teachers try to teach tricky words using repeated visual exposure – whole word imaging or memorising – but research indicates that this is not the most effective approach. This blog will discuss the flaws of the ‘whole word’ approach to the learning of tricky words and suggest more appropriate teaching/learning strategies.

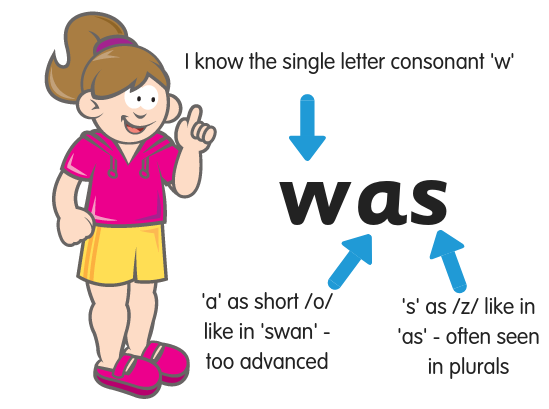

A word may be temporarily tricky. The student who has been taught only single-letter short vowel representations and the most common single-letter consonant representations will struggle to read and write some of the words commonly seen in basic sentences, such as ‘I’, ‘the’, ‘my’ and ‘was’. They will appear to be irregular to the student until the child is taught more of the advanced code.

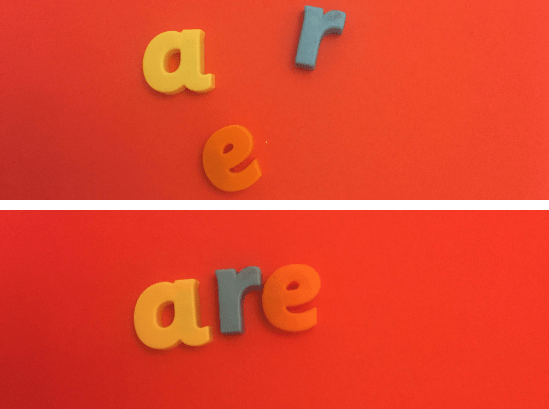

Tricky words – high frequency but tricky to decode when a child has less of the phonics code.

Tricky words – high frequency but tricky to decode when a child has less of the phonics code.Once the student has learned those letter-sound correspondences, the word will no longer be tricky or seem irregular. High-quality explicit synthetic phonics readers often list the temporarily tricky words they contain on the inside cover. These words are explicitly taught before the child reads the book.

Some words are permanently tricky. These are the irregular words (sometimes called ‘rule breakers’ or ‘exception words’). They cannot be completely encoded or decoded phonetically, even by advanced learners. However, only about 4% of English words have a completely irregular spelling, such as ‘eye’. Many irregular words are decodable except for just one letter. E.g. ‘friend’.

As I once heard someone say,

‘Sight word’ is a goal, not a quality of a word.”

A sight word is essentially any word a person recognises automatically, without effort. It is not a word that has to be learned by visual rote memory. Words become sight words because of the number of times we see or write them in context. All words, regular and irregular, become sight words for competent readers.

Fluent readers appear to be ‘reading by sight’, using a straight visual-lexical pathway. Consequently, for many decades, teachers have been expected to teach their students a ‘sight word’ list, the most well-known being the Dolch and the Fry lists. These are actually lists of high-frequency words, the words most frequently seen in written text, therefore most likely to become ‘sight words’ first. The first 100 words from Fry’s list make up 50% of the words children read. Typically, teachers have taught children to learn and recall these words as wholes rather than to decode or encode them phoneme by phoneme. Children have been asked to memorise the word shape or salient visual features and have been ‘drilled’ with flashcards.

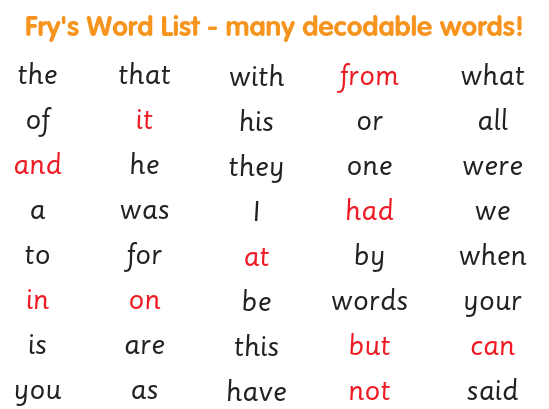

Some high-frequency words contain only standard letter-sound correspondences so are totally decodable and should not be taught as sight words.

Fry’s word list – words in red are perfectly decodable even before consonant digraphs are taught and should not be taught as a ‘sight word’. The words ‘that’, ‘with’, ‘this’ and ‘when’ are perfectly decodable once digraphs are taught.

Fry’s word list – words in red are perfectly decodable even before consonant digraphs are taught and should not be taught as a ‘sight word’. The words ‘that’, ‘with’, ‘this’ and ‘when’ are perfectly decodable once digraphs are taught.Others contain more advanced letter-sound correspondences and are tricky e.g. ‘was’ or ‘you’. Regular and irregular words on the sight word lists have been (and still are!) taught in exactly the same way – a nightmare for students with deficits in visual memory and/or rapid, automatic naming.

The practice of teaching words as whole words, be they regular or irregular, is flawed. Brain imaging studies undertaken since the 1990s have shown us that strong readers use the language and auditory centres of their brains as they read, decoding each sound so quickly that it appears instantaneous. They are not reading whole words – they are decoding the sounds in each word in milliseconds. According to Stanford research by Brian McCandliss, investigating how the brain responds to different types of reading instruction, beginning readers who focus on letter-sound relationships increase activity in the area of their brains best wired for reading (in the left hemisphere). In contrast, whole word learning is biased toward processing in the right hemisphere, the side of the brain that processes pictures and is typical of struggling readers.

You need to teach about 44 sound-letter correspondences and the skills of blending and segmenting, for phonics to make it possible to read and write 95% of all words. How many sight words do you need to teach to make it possible to read and write 95% of all words? Learning one word as a whole word/shape does not help the student learn other words. Consequently, this practice is inefficient, time-consuming and frustrating for students. It encourages students to be ‘word guessers’ when a word is not automatically recognised. There are minor visual differences between some words e.g. ‘though’, ‘thought’ and ‘through’. Without using knowledge of sounds, it is difficult to memorise them and not mix them up. The fastest, most efficient and reliable way to learn sight words is with phonics.

Teachers should distinguish between words that can be completely decoded using letter-sound correspondences and those that cannot. Words that can easily be decoded and encoded phoneme by phoneme require less teaching time than the tricky, irregular words.

The irony of the teaching practice of presenting irregular words to be learned as unanalysed wholes is that exception words require more letter-sound and phonemic analysis than regular words, not less”.

David A.Kilpatrick, 2015, Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties

I like to use the term ‘tricky’ rather than ‘irregular’ with young children when talking about words that cannot be fully sounded out, because, as I mentioned before, some are only temporarily tricky. The word ‘tricky’ is also more intriguing than ‘irregular’ because tricks are usually fascinating and something that a child would like to master. The Orton-Gillingham program refers to tricky words as ‘red words’. The red alerts the student to the fact that these words cannot be sounded out in full. The tricky bit is written in red and the rest of the word in green.

The tricky words chosen for teaching should be those most helpful for the immediate reading or writing of an otherwise decodable text. A school should move students through a sequence of tricky words that all teachers follow until the words are mastered. Phonics Hero teaches tricky words in Part 1 and Part 2 of the games and Phonics Lessons. The number of words taught each week should reflect the student’s capacity for recall.

Tricky words should not be taught as whole units. Active analysis of words helps to put them into long term memory.

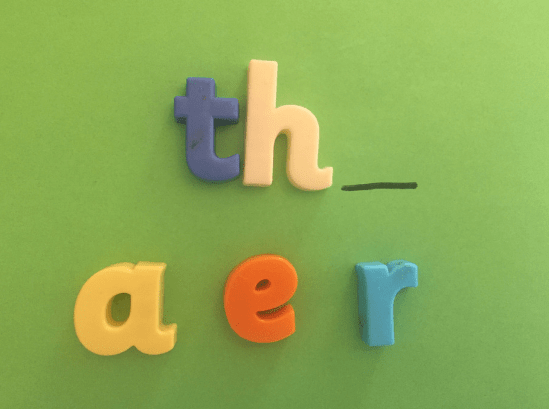

Step 1: Read the tricky word to the student(s), then read it together. Say the word again, phoneme by phoneme, representing each sound with a counter in sound boxes. E.g:

Step 2: Identify the regular letter-sound-correspondences in the word. E.g:

Step 3: Identify the ‘tricky’ bit. In the word ‘many’, the short /e/ is represented by an ‘a’. Have the student(s) read then write the tricky word, using colour to highlight the tricky bit (red or a colour more meaningful to the student).

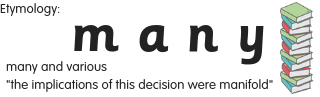

Step 4: If there is a reason for the unusual letter-sound correspondence that you are aware of, explain it. Explain the language origin, the etymology, the base word etc. E.g., ‘many’ is a short form of ‘manifold’ so is spelled like that word. English words don’t end in ‘i’ so the ‘i’ was changed to a ‘y’. The pronunciation of the ‘a’ was changed over the years.

Step 5: If appropriate, teach the student to use his ‘spelling voice’ in saying the tricky word, e.g. ’man-y’ (this is actually how some Irish people pronounce the word, so I get students to say it with an Irish accent!).

Step 6: Where needed, teach the student a mnemonic that will help him learn the tricky word. For example, there is a basket-shaped letter, ‘u’, in the middle of ‘buy’, which helps the student to remember that this homophone is associated with shopping.

Our Phonics Lessons include the teaching of tricky words for both reading and spelling. They’ve got the sound buttons, pictures to develop vocabulary and over 250 sentences using the target – everything you need to systematically teach them.

If there are other words with the same tricky pattern, teach these alongside the initial word, as a set. For example, if teaching ‘could’, teach ‘would’ and ‘should’. In the Dolch list, ‘could’ is assigned to Grade 1, ‘would’ to Grade 2. The word ‘should’ does not appear at all. This makes no sense. We want to help students to see letter patterns.

For some students, a tricky word is easier to remember if they draw a picture into it. E.g. the ‘o’ that isn’t heard in ‘leopard’ might be more easily remembered if there were lots of spots drawn on the named animal.

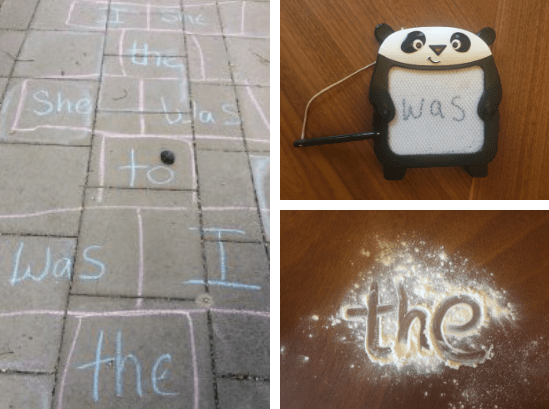

Automaticity in encoding and decoding of tricky words is easiest to achieve when multi-sensory activities and opportunities to ‘overlearn’ are provided.

An example from Phonics Hero: this game targets the /ck/ sound and highlights the tricky words.

An example from Phonics Hero: this game targets the /ck/ sound and highlights the tricky words. Write words in flour or foam, play Hopscotch or magnetic writing.

Write words in flour or foam, play Hopscotch or magnetic writing. Mix and fix those tricky words.

Mix and fix those tricky words. If children’s handwriting is still developing, use magnetic letters for ‘Word Detective’.

If children’s handwriting is still developing, use magnetic letters for ‘Word Detective’.When the student feels that he is developing automatic recall, encourage the student to self-assess by looking, saying, covering, visualising and writing the word, saying the letters. He can then check what he has written by comparing it with the original.

The teaching of tricky or irregular words should be much more effective, efficient and interesting than the ‘Drill and Kill’ practice of teaching each irregular word as a whole, on its own, out of context and with no reference to phonics. Tricky words are an opportunity (or challenge) to do word study, to teach about the many layers in our words: sounds (phonology), spelling (orthography), meaningful parts (morphology), function in a sentence (syntax) and meaning (semantics).