English is an official language in 67 countries. While all English speakers use the same 26 letters to read and write words, they do not always say words the same way.

Standardised pronunciation of ‘leisure’ in the UK…

Standardised pronunciation of ‘leisure’ in America…

There are said to be at least 160 distinct English dialects throughout the world. Each dialect has its own vocabulary, grammar rules and distinct way of pronouncing words (accent). If you use a language, you have an accent (though you might not think that you do!).

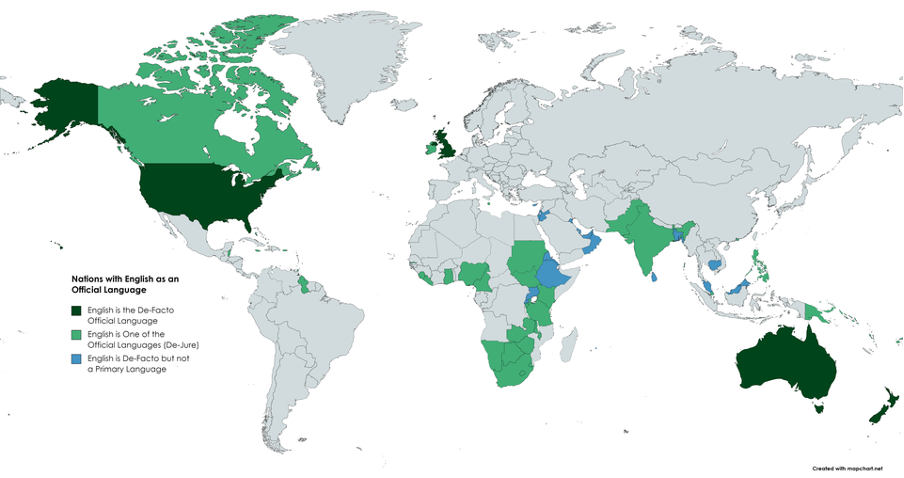

English is an official language in over 86 countries – think of all the accents!

English is an official language in over 86 countries – think of all the accents!A difference between the accent of instruction and the accent of a student has the potential to cause some students difficulty in learning to read and/or write. When phonics instruction is informed by accent, teachers can respectfully acknowledge any differences and minimise the difficulties that may arise from them.

There is no such thing as a “good”/”right” or “bad”/”wrong” accent. Class, ethnic and regional differences, as well as immigrant language influences, can contribute to accent differences. Consequently, accent can be an important part of a person or region’s social, cultural and historical identity.

I was told to ‘change my accent’ by a very southern lecturer… I have been a very successful teacher in a school with many different accents. We celebrate diversity and that should be extended to accents.”

Jane McDonald, Teacher

A 2016 study in the south of England found that many teachers with regional accents have been encouraged to “modify accents that were somehow deemed inappropriate for education”. As one participant put it, “it makes no sense that teachers have to sound the same, but teach the children to be who they are.”

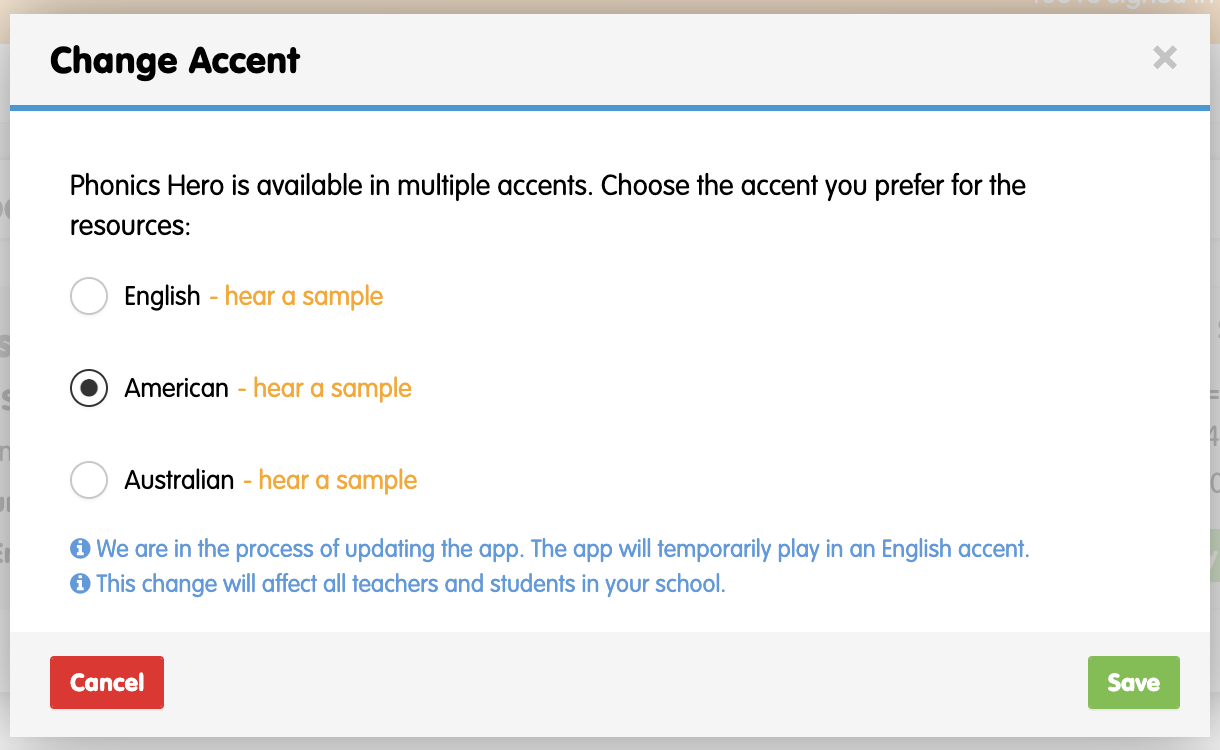

The goal of pronunciation is to be understood, not for everyone to sound the same! For educational purposes, the English language’s phonics system has been standardised and is known as the ‘Received Pronounced’ (RP) English. It is used in the phonetics of English dictionaries and translation dictionaries. The American English equivalent is known as General American (GA) and Australia has Standard Australian English (SAE).

Children usually acquire an accent by copying the pronunciation of words spoken by adults and other children around them. The more a person is exposed to an accent, the more likely they are to understand the accent. Standardised pronunciations are important touchstones for children learning to read and spell, something teachers should reference while respecting the diversity of accents found in their classrooms and beyond.

Teachers should:

To help you identify specific differences between one accent and another, I’m going to draw your attention to some common differences and give you some examples.

In English, the biggest difference between one accent and another is typically in how vowels are pronounced. Differences may be caused by the degree of jaw drop, the rounding or relaxation of lips, the raise or relaxation of the tongue or the amount of air flowing through the nose.

The GA accent has a total of 16 vowel sounds, while RP and Australian English have 20-22 (some short, some long). GA is commonly described as having short vowels and wide diphthongs. The mouth is typically more open in GA than in RP.

Common accent differences in vowel pronunciation include:

Consonants are more likely to be similar in pronunciation from one region to another than vowels, but there are some exceptions. Common accent differences in consonant pronunciation include:

In some non-standard accents, certain phonemes may be deleted. The most commonly deleted are:

In some accents, phonemes are added to words, sometimes creating an additional syllable. My Australian husband laughs when I say the word ‘film’ as /fill-um/, with two syllables. That’s the pronunciation used in the region of Northern Ireland in which I grew up!

Some accents, such as the Southern American accent, feature ‘vowel breaking’ when the short vowel in a word is turned into a diphthong. The resulting sound preserves the original vowel but it is preceded or followed by a glide so ‘cat’ can become /ca-yut/, with two syllables.

There is no community expectation that students will all sound the same when they read aloud. Consequently, the impact of an accent on a student’s reading accuracy is potentially less than that on spelling accuracy in which identical products are expected. English texts are written in either British or American English, neither reflecting regional characteristics. There are some visual differences between the two – for example, American English uses ‘or’ rather than ‘our’ (as in ‘color’), ‘er’ rather than ‘re’ (as in ‘center’), ‘z’ rather than ‘s’ (as in ‘recognize’) and ‘l’ instead of ‘ll’ (as in ‘traveling’). This is because American English spellings are mostly based on how a word sounds when spoken while British English retains the spelling of words absorbed from other languages.

When you see this (grapheme), your mouth says…(phoneme).”

This format is also useful in discussion about individual accent differences.

Where the accent of a reader may affect reading-related performance is in tasks in which students are asked to match rhyming words or to identify words with similar sounds. The problem? What rhymes in one accent may not in another.

Been doing poems in Y6 and the teacher said mud and wood do not rhyme. But mud and flood does. We’re in Greater Manchester but he’s from Essex.”

Carol, Teacher, Facebook

Consequently, teachers should be aware when tasks and tests may be biased against speakers whose accent does not match the accent of the person who wrote the material.

All English speakers, regardless of accent, are expected to spell words in the same way, using the conventions of either standard British English or American English. Certain features of some accents can reduce spelling accuracy if students are taught to write what they hear themselves say. Phoneme or syllable addition or deletion are likely to have the greatest impact. If a student’s accent is adversely affecting their ability to spell accurately, you must intervene. Show students how to modify their pronunciation when this is helpful for spelling.

Happily, research suggests that, for most students, accent differences do not significantly impact reading and spelling performance. Although they may impact students with specific learning difficulties or auditory processing difficulties, lack of explicit and systematic phonics instruction has a much greater impact.

If you are prepared to explain the subtle differences between a standard accent and a particular non-standard-accent – ideally, this blog post will have added several tools to your teaching kit! – and use high-quality phonics programs that model standardised accents, you can teach reading and spelling with confidence.