Whether you’ve just started implementing phonics in your class or are well underway, you’ve probably identified the “Do’s” for successful programme implementation, but what about the equally impactful ‘Don’ts’ of lesson planning?

As phonics veterans among us will know, when implementing a new phonics programme even teachers experienced in phonics instruction will have to navigate the obstacles that come with planning your own phonics lessons from scratch.

So without further ado, here are my Top 10 Phonics Pitfalls – and my tips to avoid them:

Phonics is, of course, about spelling as well as reading. However, many of the more appealing phonics activities tend to be reading-based, so it’s very tempting to focus on these. Look at your weekly phonics plan and add up the number of segmenting activities, then divide by the total number of activities. What is the balance of reading activities to spelling activities each week?

You might be as shocked as some of the teachers I did this exercise with in England were when they found that only 3/20 (15%) activities in phonics lessons each week were spelling focused (and they wondered why the children’s progress in reading was significantly better than in spelling!).

The Phonics Lessons from Phonics Hero give teachers the support to systematically teach spelling as well as reading. You can move through the five-step process, or remove the support, so children spell decodable words independently. Watch this 4-minute guided tour of it in action:

It’s so very tempting to fall back on asking, “Who can think of a word that’s got /[insert sound]/?” This sometimes happens when staff haven’t planned the words they are going to use within a lesson. There are a number of reasons to avoid this approach:

Make sure you plan all the words that you’re going to use within each lesson. The lessons in Phonics Hero provide differentiated words for every phoneme you need to teach – you’ll never get stuck thinking of a word or spend hours coming up with word lists.

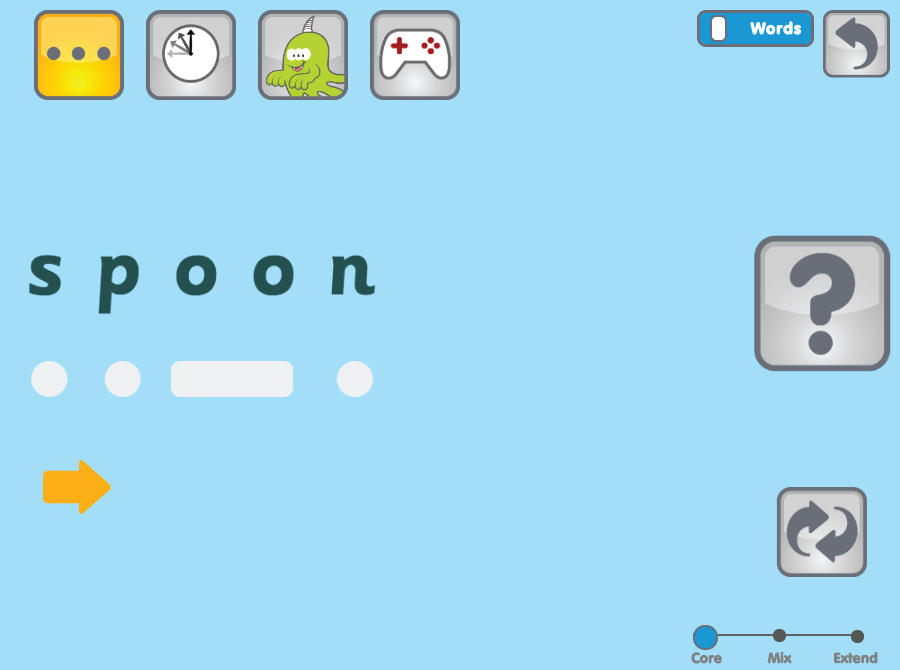

A ‘Core’ /ai/ word in Reading.

A ‘Core’ /ai/ word in Reading.

An ‘Extension’ /ai/ word in Reading.

An ‘Extension’ /ai/ word in Reading.

It’s easy to focus on the grapheme you’re teaching in a lesson, but just because a word contains that grapheme doesn’t make it a suitable word to use. It could have other graphemes which prevent it from being fully decodable at this point in the sequence. For example, ‘church’ is not suitable to use in the ‘ch’ lesson if ‘ur’ hasn’t yet been covered, ‘playground’ is not suitable to use in the ‘ay’ lesson if ‘ou’ hasn’t yet been taught. I have seen this mistake many times over the years.

When using the Phonics Hero lessons, the words are provided for you, all of which will only contain previously taught graphemes.

The lessons only include 100% decodable words.

The lessons only include 100% decodable words.

The following lesson structure is used in the Letters and Sounds programme in England:

Revision can (and should!) be included in parts 1, 3 and 4 (2 is just about the new learning). Unfortunately, many lessons I observed only included revision in part 1, with parts 2, 3, and 4 all focusing on the new learning. This resulted in some missed opportunities.

If all the words in ‘practise’ include that day’s new grapheme, the children don’t have to think too hard – it’s obvious which grapheme they need to use in each word (and that will often be left in sight somewhere from the ‘teach’ part of the lesson). Whenever possible, try to include one or two words which revise previous learning within the same activity.

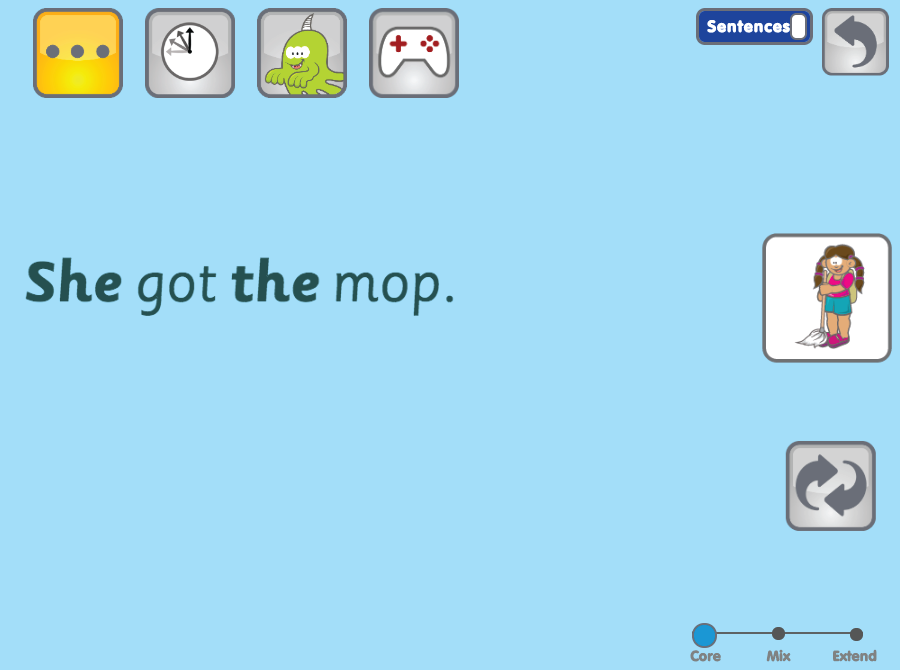

The ‘Apply’ part of the lesson usually requires the children to read or write a sentence containing the new learning. When planning this sentence, try and avoid having two words containing that day’s GPC. Aim to use one and include another word containing a recently taught grapheme which needs practice, as well as a recently taught tricky word (if at all possible). Keep the sentence as short as you can – these 3 core things can be covered with minimal words.

Choose from over 2,000 ready-made and differentiated

Choose from over 2,000 ready-made and differentiated

Many practitioners start phonics lessons with grapheme flashcards and these can be very effective. However, you need to ensure you are starting some of your lesson by revising other aspects of phonics which also need practice. This includes writing graphemes, reading tricky words, writing tricky words, blending, segmenting, recapping ‘best bet’ grapheme choices for spelling, etc.

Something I rarely saw being revised at the beginning of lessons was the spelling of tricky words (the more practice children get, the less tricky they’ll become).

Children will encounter these words when reading books and will also need to spell any that occur in their own writing. They need to be shown how to break them up into syllables and then each syllable into phonemes. If they try to tackle a long word in one go (either for reading or spelling), it is highly likely they will make mistakes.

When looking at lesson plans in English schools, I often found there were few polysyllabic words in evidence. When a new grapheme has been taught and the children have blended a few short words together, consider finishing that part of the lesson with blending a polysyllabic word containing that grapheme. Regularly include these longer words in the other parts of phonics lessons for revision purposes.

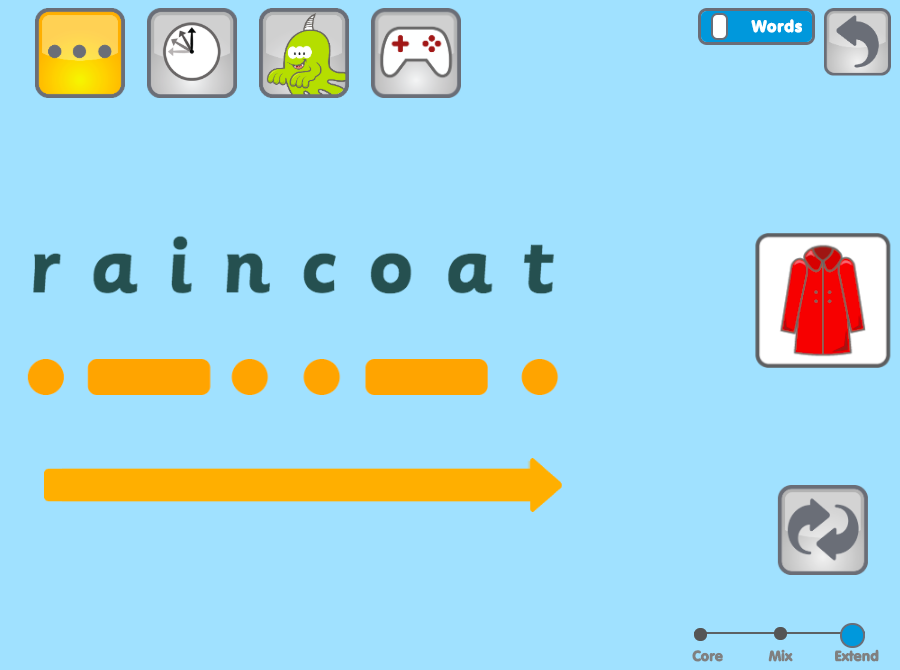

To find polysyllabic words in the Phonics Lessons, move the slider (bottom right) from ‘Core’ to ‘Extend’ and toward the end of the bank of words you will find these words.

To find polysyllabic words in the Phonics Lessons, move the slider (bottom right) from ‘Core’ to ‘Extend’ and toward the end of the bank of words you will find these words.

Asking children to “read a word” during a lesson tests what they can already do and may result in the more advanced readers calling out the word, whilst the other children don’t learn how to read it. Encourage active blending of words by all children. This includes tricky words, which are no longer taught as ‘sight words’. You can do this by putting sound buttons underneath the words you suspect children will need help with and using that as a cue to blend.

In the Phonics Lessons, the Tricky Words also have sound buttons included.

In the Phonics Lessons, the Tricky Words also have sound buttons included. It’s the same for spelling. Asking children to ”write a word” tests whether or not they can do it, rather than teaching them how to spell it. Instead, try saying the word and then getting all the children to orally segment that word on their fingers before attempting to write it.

Afterwards, you can choose a common mistake (anonymously), write it on your board, get everyone to blend what you’ve written and help you to correct it.

Most phonics programmes start by teaching children the sounds represented by each single letter of the alphabet, as this is what the children will need to start reading and spelling words (the letter names won’t help with this).

Once the sounds of the single letters have been taught, many programmes move onto teaching the names of the letters. These are generally used when discussing letters which are needed within a digraph. For example: Which letters do we need to write /ai/? The answer is the letters names ‘A’ and ‘I’, not the phonemes /a/ (like in ‘ant’) and /i/ (like in ‘ink’). Avoid using sounds of individual letters in this instance, as it is unhelpful.

Make sure you know when letter names are introduced in your programme, so you can start using them at the appropriate time.

You can read more about why letter names are generally introduced after sounds in Shirley Houston’s blog post.

Mnemonics are memory aids which help children (and grown-ups) retain key information.

Budget-friendly mnemonics from Spelfabet.

Budget-friendly mnemonics from Spelfabet.The Letters and Sounds programme in England didn’t provide any mnemonics, but teachers found some children were struggling to remember the graphemes, so looked for something that could help. For many years, there were limited options and teachers had to come up with their own. Interestingly, the vast majority of the new programmes in England do now include mnemonics for the graphemes taught in Reception (with a few going beyond and covering the Y1 graphemes).

Some single-letter grapheme mnemonics also incorporate a story, which teaches the formation of the letter. These have a dual purpose, which makes them particularly useful.

Mnemonics aren’t just for remembering GPCs; they can also be used to help children recall the spellings of tricky words. To be effective, these need to start with the word children are trying to spell, as that is what they will be thinking of at the point of spelling. Feedback I have received shows that spelling mnemonics for tricky words are highly effective for all learners (including those in the lowest 20%). Shirley Houston also mentions the use of mnemonics in her article on how to teach tricky words

If your programme doesn’t provide any mnemonics, you could create your own or consider purchasing a set.

There comes a time when children will know a number of different graphemes to represent a particular sound. They may know that ‘a’, ‘ai’, ‘a-e’, ‘ay’, ‘ey’ all represent /ai/, but how do they know which of those graphemes to use when writing /ai/ within a word?

Certain graphemes are ‘better bets’ than others in particular positions in short words. Eg ‘ai’ and ‘a-e’ are both possible at the beginning/middle of a word, whilst ‘ay’ is the ‘best bet’ at the end of a word (with ‘ey’ used very occasionally). You can investigate these spelling patterns with children by sorting words with a common sound according to where they hear the sound and then looking for patterns. Your ‘best bet’ findings should be recorded in a simple visual aid and referred to when you are modelling spelling choices moving forwards.

Some mistakes with ‘best bets’ are better than others. For example, spelling the word name as ‘naim’ is plausible using the ‘best bet’ rules above, whereas ‘naym’ and ‘neym’ are not. The latter are the ones worth discussing in more detail with the children. Where two graphemes are possible, encourage children to write out both options and see which one looks right. This is what good adult spellers do, and it is an effective spelling strategy to encourage. As children’s reading progresses, they will get better at recognising when a word looks right.

I wish you all the best in creating lesson plans for your new phonics programme and hope the above tips make planning – and teaching – easier for you. Good planning takes time, but devising a structure or template to follow using the advice above should make this more straightforward, your teaching more effective, and enable your students to make greater progress.

Happy planning!

*Answers to the question in #2 above: work, worm, word, worth