How long should a phonics lesson be? Some teachers run 15-, 20-, 30-minute or even 40-minute lessons and the school timetable often dictates the amount of time allocated. This blog will explore other important aspects of planning and explain why I recommend teachers run a discrete 30-minute phonics lesson daily.

Of course, teachers are expected to adhere to school timetables but this alone shouldn’t decide the length of a lesson. Timetables often reflect:

teacher availability (classroom or specialist)

resource availability (e.g. which class has the computers)

the number of subjects to be taught

the volume of content in each

the time requirements (e.g. minimum of two hours per week of physical education)

and the inclusion of special days/events.

A teacher’s time allocation to explicit phonics instruction should reflect research-based knowledge of pedagogy, content and the way in which a particular group of students learns best – taking children’s attention span, retention of information, speed of processing and skill level into consideration.

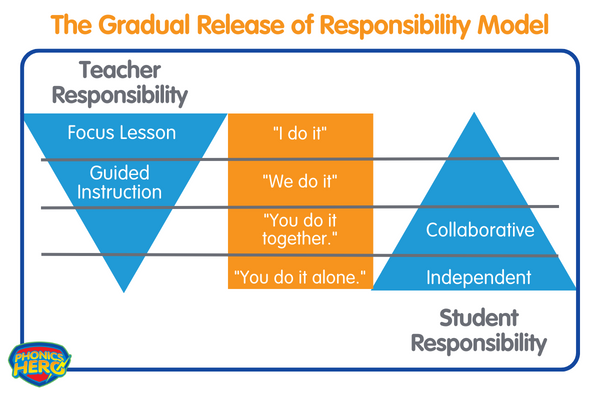

An explicit phonics lesson should incorporate modelled (direct), shared, guided and independent learning. The Gradual Release of Responsibility Framework is a best-practice instructional model in which the responsibility in the learning process is strategically transferred from the teacher to the students (Douglas Fisher & Nancy Frey, 2006). It ensures that students are supported in their acquisition of the skills and strategies necessary for success.

Typically, this model of teaching has four phases:

I Do: Direct, focused instruction in which the teacher establishes the lesson’s objective and demonstrates or models the skills or concepts, thinking aloud.

We Do: Guided instruction in which the teacher and the students work together, with the teacher scaffolding (asking questions, prompting and providing cues).

You Do It Together: Collaborative learning in which students work together, monitored by the teacher who may provide additional guided learning if needed.

You Do It Alone: Independent practice in which students apply what they have learned, completing tasks and activities to develop fluency on their own.

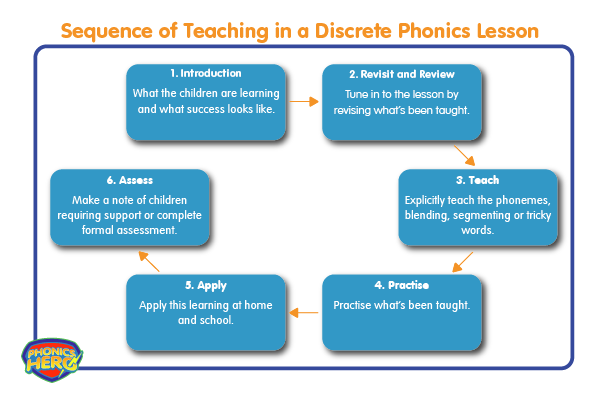

For this model of instruction to be most effective, students should experience all four phases in a single lesson. In a three-phase interpretation of this framework, the two ‘You Do’ phases are combined into one. In the Letters and Sounds Framework, on which many systematic synthetic phonics programs – including Phonics Hero – are based, these phases are referred to as Teach, Practise and Apply.

According to childhood development experts, it is generally reasonable to expect that the attention span of a child is two to three minutes per year of their age. So, in the early years of education, attention is likely to be around ten to twenty minutes. With this in mind, some schools provide 10-minute phonics lessons in Kindergarten/Reception and build to a 30-minute lesson as content becomes more complex and the ability to sustain attention increases.

Stanislas Dehaene, author of How the Brain Learns and Reading in the Brain, argues that attention is a teacher’s most important consideration. However obvious it may seem, Dehaene points out that to learn something one must be paying attention to it. Active engagement is needed to ‘wake up’ the brain and ’start the generators of learning’. If the length of a lesson exceeds attention span, the student is likely to lose focus and retain less of the lesson.

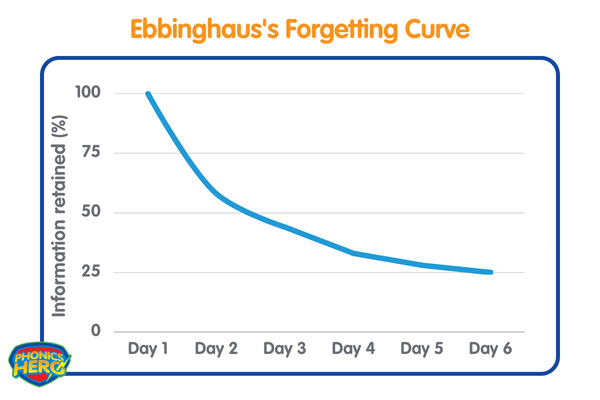

To move new knowledge and skills from short-term memory to long-term memory, learners require sufficient rehearsal, practice and review with multiple exposures over a number of days (or even weeks). Novice learners require more revision and review than a more experienced learner and a student with a specific learning disability, such as dyslexia, will need more repetition and review than a neuro-typical peer due to specific memory deficits.

The Letters and Sounds framework, shown above, recommends ‘Revisit and Review’ as Step 2 in a phonics lesson to activate prior knowledge. It also recommends that learning be assessed against criteria in the last step of the lesson. This is another form of review in which the teacher checks for understanding and ensures that the teaching goal has been achieved.

As shown in the diagram above, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus posits that the percentage of new information being retained by students is potentially increased by short lessons with repetition of new content over two or three days. Just as the first and last act of a concert tends to be the most memorable, information presented at the beginning and end of a learning session tends to be retained better than information presented in the middle.

In a lesson of around 20 to 30 minutes, the downtime between the two prime times is less than in a longer lesson. Therefore, a phonics lesson of 40 minutes or longer is not ideal for retention.

An explicit synthetic phonics lesson should include the following:

Phonological awareness

Letter-sound correspondence

Blending skills

Segmenting skills

Irregular/tricky words (introduction or review)

Reading of decodable text

Writing of decodable text

Children systematically practice the phonemes, blending, segmenting, tricky word read and spell and sentences to unlock a hero!

Children systematically practice the phonemes, blending, segmenting, tricky word read and spell and sentences to unlock a hero!

It would be difficult to incorporate all of the above in 20 minutes, let alone 15! You can find more detailed information on how to structure a phonics lesson, incorporating the above, in my blog post, A Great Phonics Lesson Decoded.

Processing speed is the ability to automatically process information. It involves the ability to take in information, understand that information and then formulate a response. When the pace of instruction exceeds the student’s ability to keep up, the student may lose concentration, become overwhelmed and be unable to learn or complete set tasks.

A teacher must be aware of the processing speed of students and slow down the pace of instruction for those who process information more slowly. This means that what one teacher can teach in 20 minutes might take another teacher with different students 30 minutes to teach.

My phonics lessons with students who have dyslexia, a specific learning disability often associated with low verbal processing speed, will usually take longer than those for neurotypical peers.

Based on results from current research, focused, explicit phonics instruction should take 30 minutes daily in primary classrooms. Literacy expert Dr Timothy Shanahan looked at 18 studies of successful phonics instruction which ranged in time allocation from 15 to 60 minutes per day. The study’s average came out at about 30 minutes per day (the mean was 34.4 minutes and the mode and median were both 30 minutes). This includes both instruction and application of phonics skills and knowledge, both decoding and encoding.

If the timetable only allows for 20 minutes of phonics instruction, the application phase could be delayed till a later slot in the same day.

Students with specific learning difficulties may need 40 minutes of daily instruction but are likely to benefit more from two short bursts of instruction (say 20 minutes) than one long 40-minute session.

Multi-sensory games can be used effectively to break up sessions.

I recommend the Phonics Hero No-Prep Phonics Lessons as an example of 15-20 minutes of high-quality explicit synthetic phonics instruction.

Follow instruction with skill and knowledge application in 10-15 minutes of reading of a decodable reader and tasks linked to that reading.

With phonics being such a critical literacy foundation it’s so important to ring-fence this time and make sure it’s an age/development appropriate duration. I hope this article has armed you with the science, and my experience, so you can make an evidence-based decision on exactly how long your phonics lesson should be.